Is ASEAN’s Manufacturing Productivity Really Equivalent to China in the 1990’s?

Op/Ed by Chris Devonshire-Ellis

At Dezan Shira & Associates, the publisher of ASEAN Briefing, we have been actively engaged in advising and assisting foreign investors into the region for the past 15 years. That essentially came following 12 years advising clients in China. Back in 2005, we saw that our clients – often US, European, and other global manufacturers – were asking us for China alternatives. We conducted our own research, into this and found that certain markets, such as Vietnam were indeed ripe for foreign investment, and manufacturing in particular. Others, such as the Philippines, had also long been popular in the light manufacturing industry. Countries such as India were also coming online, with the added benefit of offering a large domestic consumer market. Our clients were mainly interested in the cost savings attached by relocating all or part of their production facilities to Southeast Asia, and we established our own practice in Vietnam in 2006. We followed that up with our first issue of Vietnam Briefing magazine, Global Manufacturing Moving to Vietnam.

Since then we have helped several hundred clients establish manufacturing facilities in the country, and have expanded to two offices in Hanoi and Ho Chi Min City, just to keep up with demand, while we are examining another office location in Da Nang. There has been an upsurge in interest in Vietnam due to the US-China trade issues, with many US-based companies looking to relocate all or part of their business there, as Vietnam is not subject to the high tariffs that President Trump has been happily slapping on China. I recall, though, that at the time we established in Vietnam, some of our competitors questioned whether us setting up operations in Vietnam was wise, claiming that productivity issues would never make the country as competitive as China. At the time, many manufacturing companies asked us to conduct an analysis on exactly this point: how did lower production costs equate to a reduced productivity rate? In most cases, although the productivity challenge was there, we found it could be addressed over time, with training and improved infrastructure. Today, 12 years later, that gap has almost disappeared, while the cost savings, especially within the labor force, remain. Here is an example of the current salary levels across ASEAN compared with China and India, for skilled factory workers in the manufacturing sector:As can be seen, there is still a hefty difference between salary levels in China and most of ASEAN. That differential is even larger than shown, once mandatory social welfare (which can be as much as 50 percent of salary in some places) is factored in. It adequately demonstrates the wage gap and the reason why some foreign investors – and especially the US export manufacturers – are relocating to Southeast Asia. It’s also something we at Dezan Shira & Associates have seen and experienced: today we have offices throughout China as well as Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and as mentioned, Vietnam.

Accordingly, it has been something of a surprise to read on China Law Blog that manufacturing productivity in Southeast Asia is at China levels in the 1990’s. Two articles on their blog recently state essentially the same thing, but with different arguments to support their theory. One, “Moving Supply Chains From China to Southeast Asia/South Asia: It’s Not as Easy as it Looks”, states that the region has a product defect rate as high as 40 percent, are often subject to delivery delays, and that product infringement is rampant. Of course, there are answers, mainly in hiring their firm to conduct inspections, sign off contract manufacturing agreements drafted by them, and retaining services for “monitoring activities”. They conclude: “Many buyers assume the conditions in S.E./South Asia will be basically the same as for the advanced contract manufacturing centers in East and South China, but these regions are in fact more like China in the 1990s and you must account for this in planning your new product purchase programs”.

The other article, “Moving Manufacturing From China: Where You Gonna Run?”, claims Southeast Asia doesn’t have the same investment and tax incentives as China, and again urges readers that contract manufacturing agreements are a preferable vehicle to use. They again claim that “Most countries in S.E./South Asia are at a level of development similar to that of China in the 90s.” In their historical analysis of China in the 1990’s, they also claim that for foreign investors in the country at the time, “Wholly foreign-owned enterprises and Sino-foreign joint ventures paid zero income tax at the same time Chinese owned enterprises paid a 30 percent tax. This was not an exemption for a period of years: there simply was no tax imposed. At the same time, China had not yet imposed a personal income tax, which reduced the tax burden for both local and foreign workers.” That sounds great but happens to be completely untrue.

Foreign investors did pay taxes. For some manufacturers, 100 percent of the due profits taxes were exempt for the initial two years, but the notion that foreigners were not liable for individual income tax is laughable. Although the collection was not highly monitored, and the Chinese often turned a blind eye to foreigners working full-time while on multi-entry business visas, the tax was legally payable.

The motivation for articles like these to come up with these statements appears to be to promote contract manufacturing agreements, which are a basic legal document containing terms between the buyer and the manufacturer without the buyer having to set up an operation in China, Southeast Asia, or anywhere else. It can be followed through with filing of trademarks and patents, as well as other add-on services, all between the foreign buyer and their foreign service provider. That’s one way overseas service providers that don’t have their own offices in China or Southeast Asia can get involved in Asia without having to actually be here. But in offering such limited opinions, they rather do the region down.

Other foreign-invested lawyers, tax experts, quality control consultants, and an entire industry of professionals have invested their time, resources and money into handling the transitions from China into Southeast Asia and are actively involved in the region.

It is an issue I discussed in the article “Productivity Issues When Re-Positioning Your China Business for Southeast Asian Manufacturing”, in which I described the several hundred state of the art free trade zones that have sprung up throughout the region over the past decade. These include many, hi-tech investments, by both Chinese SOEs and notably, the Singapore government, to provide manufacturing facilities to investors looking to manufacture in the region. Often these are linked to major ports, rail and airport infrastructures, and site customs, bonded areas, and even worker dormitories on the facilities.

Southeast Asia is highly competitive. We can take a basic look at available investment incentives in the region as follows:

As can be seen, Southeast Asia offers significant tax incentives for foreign investors.

Of course, it is true to say that the remote regions of Southeast Asia will have production facilities that are behind in terms of productivity, and may resemble China in the 1990’s. But as a generalization for the entire region, the premise is false. But then again, such benefits count for nothing when you are effectively in the business of selling contract manufacturing – the client isn’t investing in the country so cannot access such terms.

Contract manufacturing in Asia – the downside

There are other issues with the contract manufacturing agreements. While they are fine for smaller companies, or for one-off production, generally speaking, they are not a long term solution to sourcing from Asia. The problem with the method – which is essentially a form of outsourcing – is the lack of control over the production process. This is possibly why overseas-based commentators focus on product defect rates.

Our view is that such agreements are not suitable for use in circumstances where a higher level of operational overview is required to ensure standards are met. In short, if you are contracting a job to a contract manufacturer, you will not be able to fully control the process and methods used to achieve the desired results. You only give them the specifications of the parts or products that you need, then it is mostly up to them to decide how they will go about the production.

It is also naive to expect to be the sole client of a contract manufacturer. More often than not, one contract manufacturer will have multiple clients, probably even making the same parts or products for them. One disadvantage, if this is the case, is the matter of prioritization: during peak seasons, when all the companies have huge orders, there is no assurance that you will be prioritized by your supplier. They are also more subject to labor law infringements, and this is often seen in cases where companies make use of foreign laborers in countries overseas. Often, labor is so cheap that it is lower than the minimum wage. Or the foreign laborers may be made to work very long hours and in less than friendly working conditions.

It doesn’t help that many of these countries do not have airtight regulations and protections in place for their workers. As a result, some companies take advantage of the slack, resulting to the abuse of labor – and even human rights – of the workers. This can damage the reputation of a well-meaning but inexperienced foreign firm. Again, such contracts are suitable for short term production. But for longer-term manufacturing it makes far more sense to take control of the operations from top to bottom. And that means establishing a permanent presence in Asia to impose just that.

Establishment manufacturing vs contract manufacturing in Asia

If your need for a product from Asia is likely to be longer-term, then it is worth investing in your own facility to ensure quality and delivery times are met and by imposing your own standards on the business – something which cannot generally be done with contract manufacturing. Governments in Asia know that this requires capital investment, yet are also looking to provide their citizens with employment, and also, additional training, to allow the local economy to grow and develop hand in hand with upgrading the capabilities and wealth of the local population. This is why the tax incentives I mentioned earlier are in position to attract the investment, defer profits taxes for several years, and to provide claim-backs or exemptions from VAT and import duties.

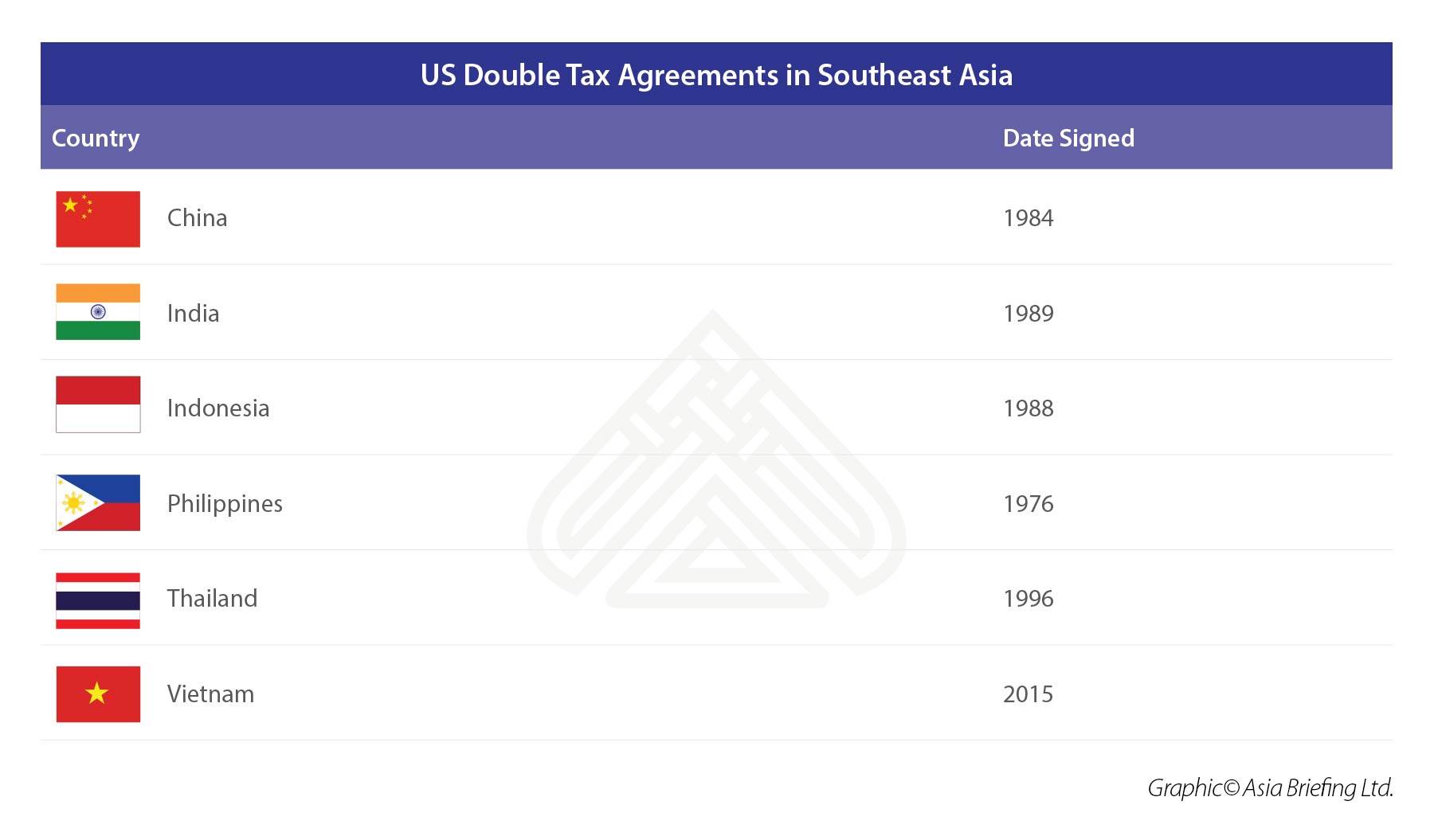

In terms of additional benefits for US-based businesses setting up manufacturing operations in Southeast Asia, it is also worth considering the status of Double Tax Agreements (DTA) the US and other countries have in place with countries in the region. A DTA can provide, when used properly, and discussed with the tax bureau at the Asia end, tax relief on profits tax and on various services and individual income tax can be claimed.

All things considered, it is obvious that claims that ASEAN is somehow 30 years backward from China are wildly inaccurate to be almost laughable. The fact that overseas lawyers seek to over simplify one of the most energetic, fast growing, and wealthiest regions in the world indicates a totally inadequate understanding of what is happening not just in ASEAN, but in Asia as a whole. We can take a look at the 2019 GDP growth in the region in two graphics below:

In terms of ASEAN trade with the US, in fact, the US-ASEAN Business Council states it is booming. In the article “Why ASEAN Matters”, they point out that ASEAN ranks fourth globally in US exports after Canada, Mexico and China. In fact, ASEAN overtook China as an export market for US products earlier this year, mainly due to the higher tariffs imposed on US exports by China as part of the retaliatory measures on the on-going US-China Trade War.

Pushing ASEAN down to promote services (such as the need to hire lawyers) is misleading. The moral of the story is, as always, don’t believe everything you read on the internet. The professional point to make is – don’t use lawyers selling services in countries they do not have an operational presence in. There are plenty of respectable, well-financed, and knowledgeable professional services firms operating in Asia. They will explain the legal, tax, and operational issues when investing in the region. Anyone else suggesting ASEAN is like China in the 1990’s is living in a time warp.

About Us

ASEAN Briefing is produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm assists foreign investors throughout Asia and maintains offices throughout ASEAN, including in Singapore, Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City and Jakarta. Please contact us at asia@dezshira.com or visit our website at www.dezshira.com.