ASEAN’s Demographic Dividend

By Shawn Greene

Nov. 25 – More than 30 years after Deng Xiaoping first introduced China’s famous “one-child” policy, President Xi Jinping’s government appears set to finally relax the country’s approach to family planning. Announcing this month that many urban couples will soon be permitted to have two children under broader exemptions to the “one-child” rule, the government’s policy shift comes amidst concerns that the country’s low fertility rate and rapidly ageing population may threaten its long-term social and economic stability.

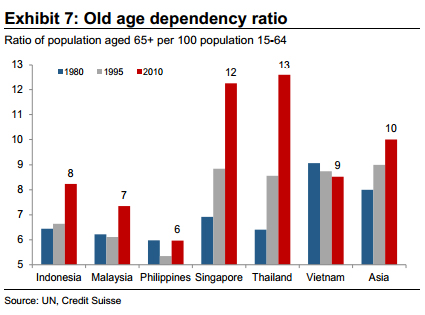

With China’s tax-paying, working-age population declining by millions each year – and its population of benefit-dependent retirees expected to reach 200 million by the end of 2013 – sustaining China’s rise arguably depends upon its fertility levels normalizing at or above the level of replacement. Many, including the Brookings Institute, characterize China’s impending demographic deficit as a severe and potentially fatal crisis for its economic growth. By 2050, even with recent changes to its family planning policy, there will be fewer than 1.6 workers for every retired person in China, and the fertility rate is predicted to remain significantly below the 2.1 children per household needed to hold its population level.

While China’s low fertility rate and controversial family planning policies are among the most well-known in Asia, China’s ASEAN neighbors also rank among the world’s lowest-fertility societies and appear poised to reap significant economic benefits from their relatively young populations and rapidly decreasing dependency ratios (proportion of young and retired to working-age adults).

Oftentimes referred to as ASEAN’s demographic dividend, ASEAN countries’ decreasing dependency ratios have the potential to translate into significant GDP growth if accompanied by effective government policies that liberalize trade, attract FDI, and mobilize capital and labor productively.

Demographics and GDP Growth

While few economists can agree on the concise effect population growth has upon economic growth, many contemporary leaders in the field of demographic economics such as David Canning and David Bloom increasingly view a population’s evolving age structure as a key determinant of real GDP growth.

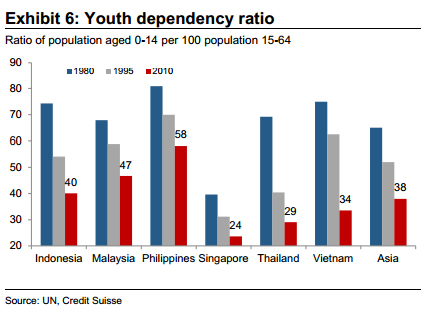

Age structure, or how a population is distributed across different age groups, determines what a country’s dependency ratio will be. While both young and old members of a population (dependent groups) require investments in healthcare, education, and retirement income, prime-age adults supply society with the labor and savings needed to support dependent groups while driving overall economic growth.

In many ASEAN countries, low mortality and fertility rates, alongside rapidly growing populations of working-age adults, will provide several countries with the opportunity for remarkable GDP growth in the next 20 to 30 years.

China and ASEAN’s Prospects

ASEAN countries are, on the whole, in a more developed stage of their demographic transition towards a lower dependency ratio. China, on the other hand, is nearing the end of its demographic dividend and will soon suffer from a demographic deficit.

In China, improvements in public health and development led to a rapid decrease in infant mortality in the 1950s. Coupled with voluntary programs that incentivized families to have fewer children, the lag between the decrease in infant mortality and decline in fertility allowed for the creation of a baby-boom generation. Between 1965 and 1990, Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms and mandatory family planning caused China’s working-age population to grow nearly four times faster than its dependent population. This phenomenally low dependency ratio is estimated to account for between one-fourth and two-fifths of China’s “economic miracle.”

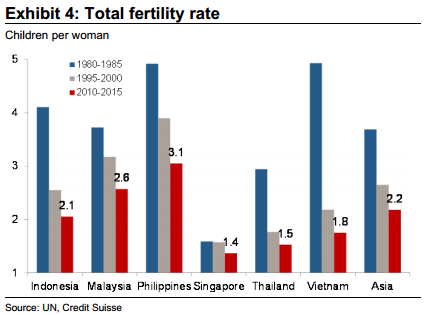

Today, however, as China’s baby-boom cohort ages, its artificially low dependency ratio (created by strict family planning policies) will translate into a severe population deficit. As life expectancy has risen from 43 years in 1950 to almost 74 years today, population growth has slowed from a fertility rate of around 5.9 in 1967 to 1.5 in 2013. Although China’s incredible economic success demonstrates the potential for rapid GDP growth to occur when demographic dividends are accompanied by liberalized economic policy, it is now ASEAN’s turn to reap the benefits of this cycle.

In Southeast Asia, relatively stable population growth rates at less than 1 percent per year shot up between 1950 and 1990 to well over 2 percent. At this rate, Southeast Asia’s working-age population will account for 68 percent of the region’s total population by 2025 – up from less than 60 percent in 1990. Alongside this shift, dependency ratios have been falling increasingly rapidly as youth dependency falls from 0.77 to less than 0.60.

While some ASEAN countries such as Indonesia have already begun to experience, and capitalize upon, their demographic dividends, Vietnam, Malaysia, and others are just beginning to experience their own demographic transitions.

Indonesia exemplifies an ASEAN country that has already capitalized upon its demographic transition through rigorous institutional development and a shift to an export-oriented manufacturing sector. Reforming its economy in the 1970s – preempting its population dividend – Indonesia has experienced between 6 and 8 percent GDP growth almost every year since enacting its market reforms. Despite this success, Indonesia continues to drag its feet on investments in education and healthcare: two possible avenues for creating a more highly skilled, healthy workforce to attract FDI.

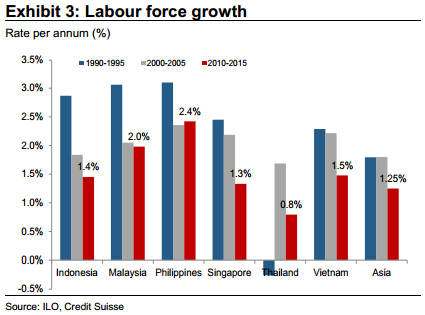

Along with Indonesia, three other ASEAN countries – Vietnam, Malaysia and the Philippines – are expected to experience double-digit labor force growth through 2020 and beyond. In Vietnam, market liberalization and government reforms initiated in 2011 will be among the first steps towards capitalizing on the nation’s growing demographic dividend and falling dependency ratio. Attracting record FDI in the past eight years, Vietnam appears set to reap significant GDP growth from its demographic transition as it continues to liberalize trade and invest more in education and healthcare.

Similarly, Malaysia and the Philippines have recently begun improving their own fiscal and monetary policies to attract more FDI and increased capital expenditure. In the next decade, the Philippines will face the largest challenge and opportunity in respect to its own demographic dividend. Its 3.1 fertility rate, the highest in ASEAN, will present the Philippines with the opportunity to expand its GDP by around 7 percent per year if it can successfully reform its trade policies and social services to attract a 30 percent increase in investment. Similarly, Malaysia’s third highest fertility rate in ASEAN (2.61) will present it with a large demographic dividend and real GDP growth if it is able to follow through with the infrastructure improvements and more transparent trade policies needed to attract FDI.

Conversely, if the appropriate policy environment is not in place, health, education, and social welfare systems will undergo significant strain, and unemployment and instability may result.

Seizing Opportunity

While a number of ASEAN countries are projected to have a large working-age population and comparatively small population of dependent youth and elderly over the next two or three decades, whether or not a country can translate this dividend into real GDP growth depends largely upon public policy.

For high-tech and high-FDI economies such as Singapore’s, demographics are not as important as they are in manufacturing, agriculture, and service-based economies such as Vietnam, Thailand, and the Philippines. If ASEAN countries want to make the most of their existing or impending demographic dividends, critical investments must be made in education and healthcare alongside an overall liberalization of trade policy.

Without the appropriate policy environment, health, education, and social welfare systems will undergo significant strains from demographic dividends, and unemployment and instability may result. Latin America’s notoriously wasted demographic dividend of the 1970s and 1980s – during which weak governance and a lack of openness to trade stalled growth – should be kept in mind as ASEAN looks to the future, and ASEAN governments continue to contemplate how to best woo foreign investment and grow their economies.

Dezan Shira & Associates is a specialist foreign direct investment practice, providing corporate establishment, business advisory, tax advisory and compliance, accounting, payroll, due diligence and financial review services to multinationals investing in emerging Asia. Since its establishment in 1992, the firm has grown into one of Asia’s most versatile full-service consultancies with operational offices across China, Hong Kong, India, Singapore and Vietnam as well as liaison offices in Italy and the United States.

For further details or to contact the firm, please email asia@dezshira.com, visit www.dezshira.com, or download the company brochure.

You can stay up to date with the latest business and investment trends across Asia by subscribing to Asia Briefing’s complimentary update service featuring news, commentary, guides, and multimedia resources.

Related Reading

Are You Ready for ASEAN 2015?

Are You Ready for ASEAN 2015?

ASEAN integration in 2015, and the Free Trade Agreements China has signed with ASEAN and its members states, will change the nature of China and Asia focused manufacturing and exports. In this important issue of Asia Briefing we discuss these developments and how they will impact upon China and the Global Supply Chain.

Has China’s Demographic Dividend Payout Ended?

China’s Demographics Point to India as Next Global Manufacturing Hub

Report: China’s 2020 Consumer Demographics

- Previous Article New Issue of Asia Briefing: The 2014 Asia Tax Comparator

- Next Article December 2013 ASEAN Regional Meetings